Imagined

Geographies

Early European maps of the world, including those of Southeast Asia, were as much fantasy as fact. They are "inaccurate" by today’s standards of geographical knowledge and positioning. How can we explain their inaccuracies?

Read Story

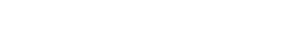

Sometimes early modern maps were simply "fantasy maps", as is the case with Heinrich Bünting's 1581 representation of Asia in his Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae. The then known geography of Asia, which excludes Southeast Asia, is ordered according to the figure of Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek mythology. Such figurative depictions were used both as an aide-memoire, to help readers remember the countries depicted, and to express symbolic meaning. Bünting’s book also included a map of Europe with the geography arranged in the form of a crowned female figure. The images reflect the Eurocentric views of the author: Europe as the "first part of the earth" is depicted as human and sovereign, while Asia is depicted in mythical animal form. The parts of Asia we today call Southeast Asia are not even depicted [1].

Asia secvnda pars terræ in forma Pegasi

[Asia the second part of the earth in the form of Pegasus], 1581 [2].

Europa prima pars terrae in forma Virginis

[Europe the first part of the earth in the form of a virgin Queen], 1518 [3].

A European Perspective

Maps reflect two key things: what is known about the world by a society at a particular point in time, and the technologies of geographical positioning and representation available. The early maps by European cartographers of what we today call "Southeast Asia", depict what Europeans knew about this part of the world at the time, based on existing accounts, written and cartographic.

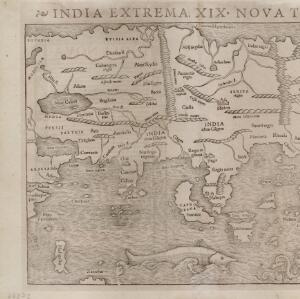

Vndecima Asie Tabvla [Eleventh Asia Map]

This map was published by Johann Reger in 1486. It is based on the second century map made by the Roman geographer Ptolemy (AD 100 – 170) [4].

Claudius Ptolemy

AD100 - 170

Ptolemy was an ancient Roman scholar who wrote a treatise entitled Geographia (also called Cosmographia). It documented, in text and maps, the known world of the time. The treatise influenced cartographic depictions of the world for centuries after. In 1533 a Greek version Geographia was published in Basel by the scholar Erasmus, likely a version already elaborated by an unknown Byzantine scholar. Ptolemy's map appears in copied and amended forms in many print publications across the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe [5].

The many maps

after Ptolemy

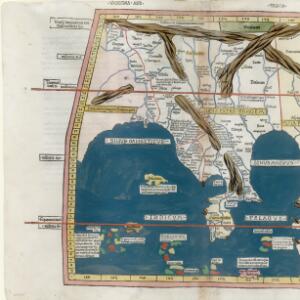

Vndecima Asie Tabvla

This 1486 version of Ptolemy's Eleventh Map of Asia was published by Johann Reger (1434-1499), a printer based in the German city of Ulm. This version used the font and wood printing blocks first used by Lienhart Holle for his great 1482 "Ulm edition" of Ptolemy's Geographia [4].

Undecima Asiae Tabula

Ptolemy's Eleventh Map of Asia is here interpreted by Italian map printer Bernardus Sylvanus (Bernardo Silvano – 1465 - unknown) in his 1511 edition of Geographia. He added details and corrected information based on current knowledge. The use of two colours in the printing (red and black) was considered innovative [6].

Vndecima Asiae Tabvla

This version of Ptolemy's Eleventh Map of Asia was published by German cartographer and printer Martin Waldseemüller (1470-1519) in a 1513 edition of Geographia. Waldseemüller drafted twenty additional tabulae modernae (modern maps), based on the latest geographical knowledge, for an supplementary appendix. This map shows the then innovative use of light green tinting to highlight the mountains and seas [7].

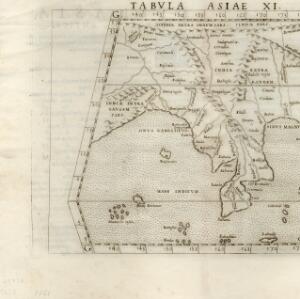

Tabvla Asiae XI

This version of Ptolemy's Eleventh Map of Asia was in a translation of Ptolemy's Geographia by the Italian cartographer Girolamo Ruscelli (1518–1566). His translation included 40 then contemporary maps based on maps compiled in 1548 Giacomo Gastaldi (1500-1566) [8].

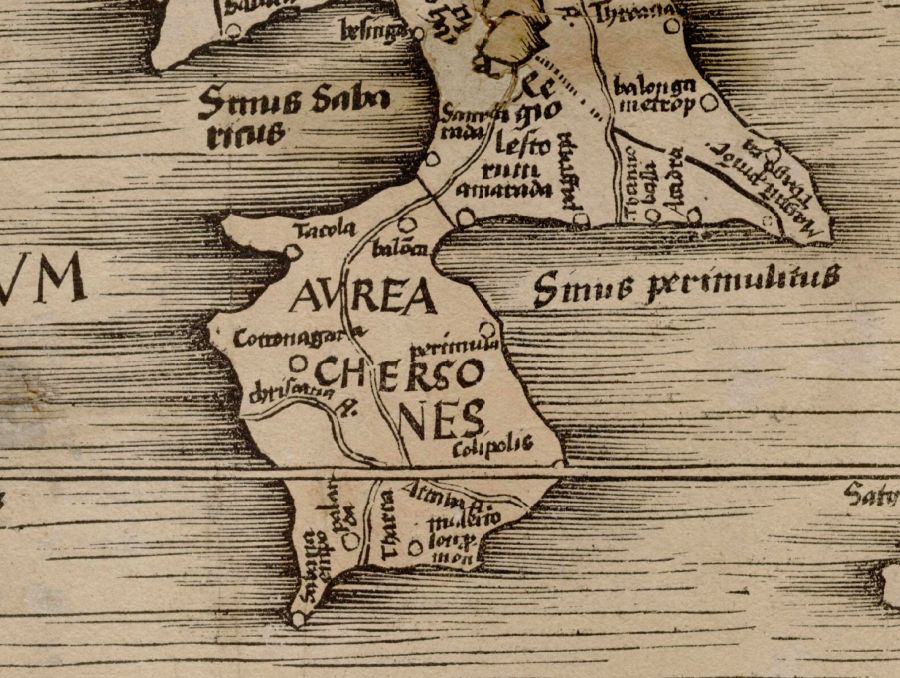

The Golden

Chersonese

Ptolemy's Vndecima Asie Tabvla [Eleventh Asia Map] depicts the territory and waters we today call Southeast Asia. In this map the Malay Peninsula is labelled as Aurea Chersonese, or "golden peninsula", referring to the precious metals reputed to be found there [9].

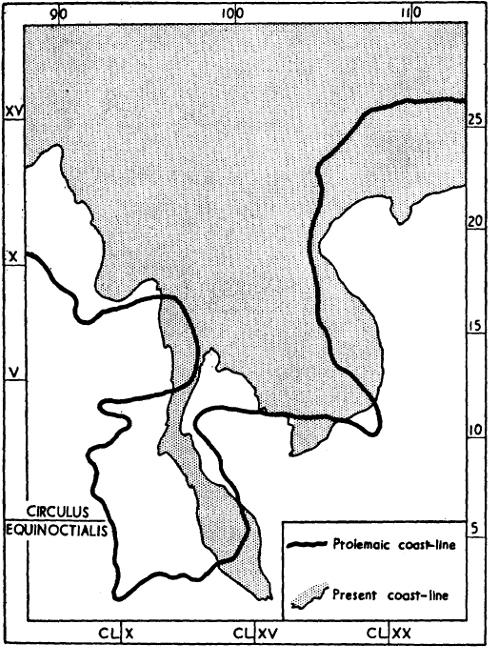

The Ptolemaic coastline of South-east Asia compared with that from a modern map [10]

Münster's Cosmographia

One Early Modern elaboration of Ptolemy's Geographia was by German cartographer Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) [11]. Münster’s Cosmographia (1544) was translated into many European languages, including a partial translation into English by Richard Eden and published as Of the New India (1553) [12]. Here we compare the opening page of the 1544 German edition of Münster's Cosmographia with the preface page of Eden’s Of the New India.

A treatise of the new India with other new found lands and islands, as well eastward as westward, as they are known and found in these our days, after the description of Sebastian Munster in his book of universal Cosmographie: wherein the diligent reader may see the good success and reward of noble and honest enterprises, by the which not only worldly riches are obtained, but also God is glorified, and the Christian faith enlarged.

Translated out of Latin into English. By Rycharde Eden.

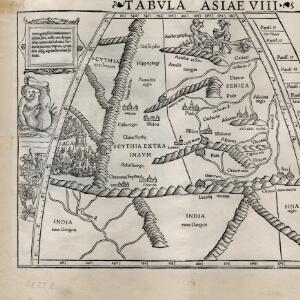

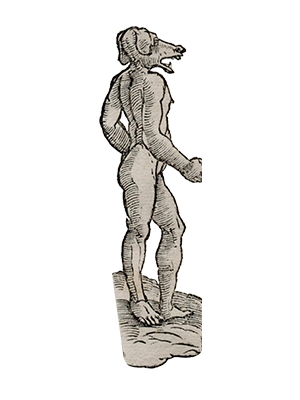

Münster's Monsters

Münster’s Cosmographia offered new knowledge about the geography and people of the world, including Asia. Tabvla Asiae VIII shows Central Asia, northern South Asia and parts of northern China and eastern China. The map is surrounded by depictions of imagined inhabitants of Asia. These “monstrous races” replicated fantasy beings first described by the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder in his Natural History (AD 77). This includes a mythical race of cannibals called Antropophagi, fast-moving one-legged Sciopods and dog-headed Cynocephali. The presence of such monsters on the edge of a map was a sign that the territories depicted were beyond Europe’s known world [13].

Blemmyiae

Bear faces on their chest

Sciopods

One-legged and fast moving

Cynocephali

Dog-headed

Anthropophagi

Cannibal tribe

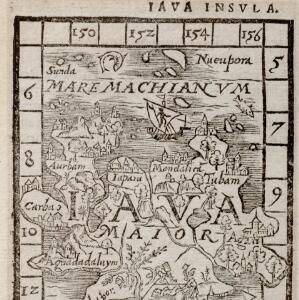

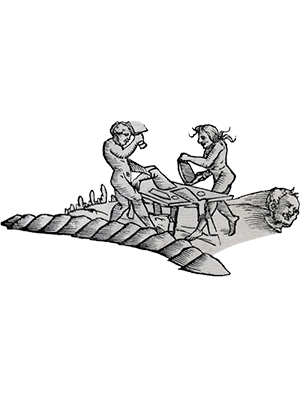

These imagined monster races included those who were seen to deviate from the moral norms of Europe, such as Anthropophagi or cannibals. In Tabula Asiae VIII cannibals are shown as inhabiting the northern reaches of Central Asia. Similar depictions of cannibals appear elsewhere in Münster's Cosmographia, including this map of Java Major. The repeated depiction of cannibals in the parts of the world then little known to Europeans, reminds us that cannibalism loomed large in the European imagination as a symbol of alterity and entrenched xenophobia [14].

Explore More

Reference

[1]

Jacob, Christian. The sovereign map: Theoretical approaches in cartography throughout history. University of Chicago Press, 2006.

[2]

Bünting, Heinrich. Asia secvnda pars terræ in forma Pegasi. 1581. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056074H> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[3]

Heinrich Bünting, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons < https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4e/Europa_Prima_Pars_Terrae_in_Forma_Virginis.jpg> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[4]

Vndecima Asie Tabvla. 1486. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055947E> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[5]

Jones, Alexander. "Ptolemy’s Geography: Mapmaking and the scientific enterprise." Ancient Perspectives: Maps and Their Place in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome (2012): 109-128. Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons <https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0b/PSM_V78_D326_Ptolemy.png> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[6]

Silvani, Bernardo. Undecima Asiae Tabula. 1511. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055955D> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[7]

Waldseemüller, Martin. Vndecima Asiae Tabvla. 1513. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055956E> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[8]

Ruscelli, Girolamo. Tabvla Asiae XI. 1561. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056097B> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[9]

Wheatley, Paul. "The Golden Chersonese." Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers) 21 (1955): 61-78; Borschberg, Peter. "Three early 17th-century maps by Manuel Godinho de Erédia." Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 92, no. 2 (2019): 1-28.

[10]

Wheatley, Paul. "The Golden Chersonese." Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers) 21 (1955): 64.

[11]

Cover of first edition of Cosmographia by Sebastian Münster, printed in Basel by Heinrich Petri in 1544, gescannt von: Michael Schmalenstroer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

[12]

Title page from Richard Eden’s Treatyse of the Newe India. Source: John Carter Brown Library at Brown University: Young, Sandra. "The "Secrets of Nature" and Early Modern Constructions of a Global South." Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 15, no. 3 (2015): 5-39.

[13]

Davies, Surekha. Renaissance ethnography and the invention of the human: new worlds, maps and monsters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016; Van Duzer, Chet. "Hic sunt dracones: the geography and cartography of monsters." In The Ashgate research companion to monsters and the monstrous, pp. 427-476. Routledge, 2017; Young, Sandra. "The" Secrets of Nature" and Early Modern Constructions of a Global South." Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 15, no. 3 (2015): 5-39. Münster, Sebastian, and Ptolemy. Tabvla Asiae VIII. 1545-1552. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056088B> (accessed June 30, 2022).

[14]

Goldman, Laurence R. "From pot to polemic: uses and abuses of cannibalism." The anthropology of cannibalism (1999): 1-26. Münster, Sebastian. Iava insvla. 1544-1552. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056119H> (accessed June 30, 2022).

[15]

Münster, Sebastian. India extrema XIX nova Tabvla. 1540. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056077K> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[16]

Hoogvliet, Margriet. "The medieval texts of the 1486 Ptolemy Edition by Johann Reger of Ulm." Imago Mundi 54, no. 1 (2002): 7-18.

[17]

Image: circa 1540 Source Album di disegni, illustranti usi e costumi dei popoli d'Asia e d'Africa con brevi dichiarazioni in lingua portoghese, Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome. Unknown author, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons: Winstedt, Richard Olof. "The Malay Annals of Sejarah Melayu." Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 16, no. 3 (1938): 1-226.

[18]

Münster, Sebastian. Treatyse of the Newe India. Translation by Richard Eden (London: S. Mierdman for Edward Sutton, 1553). http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A07873.0001.001.

[19]

Rogers, William, Jan Huygen van Linschoten, and Robert Beckit. Insvlae Molvccae. 1598. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/beinecke-1151847> (accessed June 10, 2022).

[20]

Münster, Sebastian. Die Laender Asie nach ihrer Gelegenheit biss in Indiam, werden in dieser Tafeln verzeichnet. 1550. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/beinecke-15831876> (accessed June 10, 2022).